DRONE - Making of an animated short film

A behind the scenes look at the production of an independent animated short.

INTRODUCTION

There’s a stereotype that animators are attic-dwelling loners who isolate themselves, have social anxiety, and are obsessive compulsive perfectionists as they meticulously work on their films. I generally reject this characterization. I believe that animation takes just as much work as live action, or writing, or any other creative medium when all is said and done. I love the advantage that animators have over their live-action peers to see a film through from start to finish completely on their own, it’s one of the greatest liberating benefits of using animation as a medium.

The primary disadvantage that animators face, especially independent animators working alone (and doubly especially if you live in the United States), is that the animated short film exists in a nebulous cultural space, and as a result there is little to no support, both financially and for exhibition (apart from YouTube, where it is contextualized in an endless stream alongside every other form of Internet video subculture). This all notwithstanding the fact that animation is typically relegated to the genre of Family Entertainment, and not taken all that seriously as an artistic, cinematic medium.

So why make an independent animated short? The answer to me is simple, even if the path of execution is senseless and ill-advised: animated shorts present the perfect opportunity to execute a singular or closely collaborative vision unlike any other artistic medium. This was my feeling as I embarked on the production of my animated short film Drone.

Note: In an attempt to document the process of making this film in as linear a way as possible, some chronology of dates and events might sometimes seem jumbled. Film ideas tend to develop and manifest in non-straightforward ways. If it’s ever confusing, rest assured that it was equally confusing for me too.

GETTING STARTED

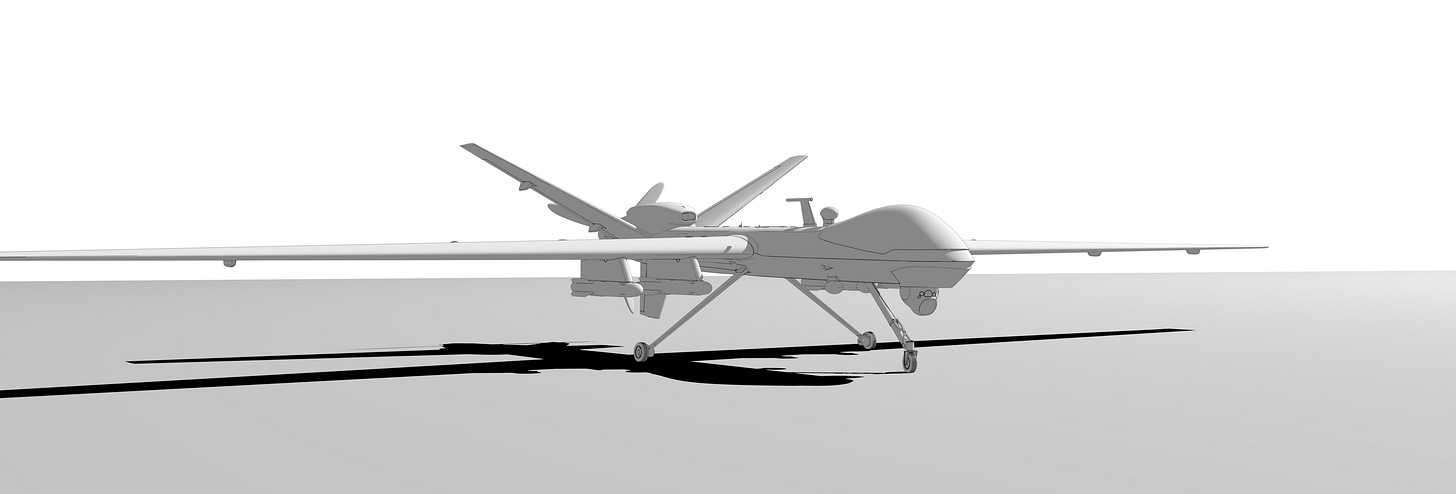

Real production began on Drone in May 2019, but the kernel of the idea goes back to 2014. I was reading the news and saw an article in The Guardian titled “Predator and Reaper drones are misunderstood, says manufacturer”.

I thought this was a funny idea: the misunderstood drone and the attempt to rebrand. In a fit of brief inspiration, I made a very lo-fi GIF in Flash.

I wrote in the post: “It’s going to be a comedy I think.” I was working on other projects and quickly moved on from the spark of inspiration, but there was a morsel there, a romantic image of the misunderstood drone flying through clouds against the sunset, that stayed lodged in my head.

Fast forward to 2017. I had recently finished my previous short, Lovestreams, which felt like a real struggle to make. Coming out of the completion of that film, I had resolved to pivot my creative energy exclusively into the more traditional animation industry. I had done freelance commercial work to help fund the production of Lovestreams, but now I was ready to begin pitching my own ideas, either as a TV show or a series of shorts (or, frankly, whatever, I just wanted to get paid to work on the stuff I cared about). This led to a disappointing six months of hitting wall after wall, never quite sure if I was on the edge of a breakthrough or intensely naive about how the process worked (or, god forbid, my ideas were just bad, or non-commercial, which might be worse).

By November, my commercial aspirations had slowed, and I began working as a storyboard artist on a TV pilot. In the midst of that job, I received an email from GIRAF, a wonderful animation festival in Canada, inviting me to come as a visiting artist and show a retrospective of my own work. I didn’t have enough personal work to fill up a whole show, so I included a couple of commercial pieces to fill out the time. Sitting through the retrospective, I was really disappointed with how the commercial work felt alongside the personal work. I could feel how worthless it was in a context that actually allowed me to represent my interests as an artist. It felt like a hollow demonstration of marketable skills and cheapened everything else I was showing.

Walking back to the hotel that night, I resolved to commit to making another personal film, but more seriously this time, like it was a real production and not just a side hobby. I was through with the commercial gatekeepers and would self-initiate every aspect of production. I would do things properly, write a script, create a watchable animatic, and rigorously apply for grants and seek out other funding for independent projects. Although this would involve a new set of gatekeepers, I hoped they would be more amenable to making a dark satirical comedy about Predator drones.

On the flight home, I wrote down the very first summary of the plot, scribbled underneath a drawing I had just made of my mom.

THE STORY

My ideation process for stories usually starts with three images that feel related, but not in a totally straightforward way. I felt like I had two big images in my head already with the drone flying through a romantic sunset and a nervous CIA agent and overzealous PR person at a press conference explaining the rebrand.

I’d always been interested in the Pareidolia effect and seeing faces in everyday objects or patterns. This became the key to unlocking the third image and the inciting incident of the story. The image that came to mind was a rock on the ground, the shadows cast across its surface creating the illusion of a face in agony. This made me think about the misunderstood drone trying to do good, but thinking it has accidentally killed a civilian seeing the face in a pile of blown up debris. With this image, the actual contours of the idea felt complete. The three pillar images form a kind of net for other ideas that might otherwise flow through you, but suddenly have a context with the other images that allow them to form connective tissue and fill out the holes and missing details of the story.

RESEARCH AND INSPIRATION

The idea of remote warfare had always struck me as an ethically dubious and abstract way of killing people (on top of the extrajudicial nature of the killings, as I’d seen in Jeremy Scahill’s Dirty Wars some years before). I was also interested in what felt like an inevitable trajectory: why would we continue to send troops abroad to fight in these not-too-popular forever wars when you could just as easily have robots killing people while the pilots sit in an air-conditioned room in Nevada? Beyond that basic understanding, I didn’t know too many details about the military drone program, so before really digging into the script, I started doing a lot of research.

What surprised (and horrified) me most digging into the research was how plausible almost every aspect of this story was from a technological standpoint, and the true stories of these incidents helped me structure the plot in the film. As Madea Benjamin describes in her book Killing by Remote Control: “Drones can also ‘go rogue,’ meaning that the remote control is no longer communicating with the drone. In 2009, the US Air Force had to shoot down one of its own drones in Afghanistan when it went rogue with a payload of weapons. In 2008, an Israeli-made drone used by Irish peacekeepers in Chad went rogue. After losing communication, it decided on its own to start heading back to Ireland, thousands of miles away, and crashed en route.”

More than anything, the research helped put into relief a lot of the themes and ideas I had already been interested in. “‘Lethal autonomy is inevitable,’ said Ronald C. Arkin [an American roboticist and roboethicist]… Arkin believes autonomous drones could be programmed to abide by international law. Others vehemently disagree and question the ethics of robots making life and death decisions… that’s why - ethical or not - the military will most likely be expanding its dependence on machines that do not possess the troublesome emotions and consciences of its human pilots.” The idea of a machine designed to make morally/ethically complicated decisions, imbued with the facsimile of emotions and consciences of a person trying to do “good”, became the central point of focus for the film. The quality of Newton’s questioning was inspired by a speech made by Dwight D. Eisenhower criticizing the newfound influence of the military industrial complex where he asked: “Is there no other way the world may live?”.

I was also interested in how this would be absorbed and interpreted by the public, and how people’s feelings and response to spectacle can also be weaponized, for better and (often, and certainly in the case of Drone) for worse.

I also drew a lot of inspiration during this time from other films and literature, which was a huge compliment to the dryness of the research. The idea of the articulate monster led me to Frankenstein, which was a huge influence on the way the drone would articulate itself. I’ve always been interested in how people can’t help anthropomorphizing things (something animators have had a healthy hand in utilizing), even when they represent something truly ugly.

“I wished sometimes to shake off all thought and feeling, but I learned that there was but one means to overcome the sensation of pain, and that was death - a state which I feared yet did not understand.” - Frankenstein

I also watched Terminator 2: Judgment Day, a perfect inversion of the killer machine trope and unexpectedly emotional when it wants to be, and Dr. Strangelove, which still feels ahead of its time to me and was extremely useful for dialing in a dark satirical tone for a nightmarishly realistic scenario.

All this research and inspiration was particularly useful as I began to write artist statements for grant applications. Although it continued to get tweaked, by the end of this initial research phase, I had developed a number of useful pieces of writing, including the official synopsis:

The CIA attempts a rebrand by installing a Predator drone with an onboard AI personality named Newton to serve as an ethical and compassionate voice to defend and justify the use of lethal force. At the press rollout, a malfunction causes the drone to go rogue. The livestream of the event is an instant viral sensation, and the world watches as the runaway drone attempts to understand its purpose in the world. On the ground, CIA personnel scramble to figure out how to salvage the situation and capitalize on the sudden rush of attention.

And a director’s statement:

The original idea for Drone was sparked by an op-ed in The Guardian from a former military general who described how the drone program had a bad image and was in need of a full rebrand. I started to imagine the marketing effort that would go into this, and how it would play out in the contemporary world. The press event where the military would attempt to rehabilitate the image of drone warfare (and how it could go disastrously wrong) seemed ripe for satire.

It is clear that we humans have a distinct inability to pump the brakes on our own ingenuity, even when it involves our own destruction or acts so morally heinous, they have to be kept at extreme distances. In his book Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology, Neil Postman argues that “Without a strong cultural and political context to determine what should be invented and why, we risked undermining both our civic culture and our democracy in the face of powerful new technologies that operated according to their own logic.” This film raises a similar question, but also inverts and recontextualizes a machine’s “own logic” as being able to more objectively judge mankind’s ethical complacency in the development of convenient and oftentimes sinister technology. The drone becomes, ironically, the only character in the film who can think rationally and humanely about his own actions; a piece of moral machinery.

My recent films have focused on the social and cultural politics of emerging technology, reflecting on the ubiquity of living in the present moment, and going on an archaeological dig for the invisible processes that got us here, imagining alternate routes to what feels like an inevitable future. Drone is more overtly political as a direct critique of American military imperialism and a piece of technology that feels, on the one hand immoral and unethical, and on the other convenient, inevitable, and resistant to any form of actual accountability, transcending partisanship in the United States as it is utilized by Democrats and Republicans alike. The film also examines the perception of drone warfare from the perspective of the American public, which, according to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center, is favored by a majority of Americans (which is shocking when compared to the nearly unanimous opposition to drone warfare by the rest of the world) and how that perception can allow for the co-opting of sincere, altruistic goals by one’s own opposition.

THE SCRIPT

I was still working on the TV pilot when I began to write the script for Drone in December 2017, which came in starts and stops. I’ve included the entire final draft of the script below, but that version represents the last stage in a long iterative process that went back and forth between writing and storyboarding, and lasted until very deep in production. The early drafts of the script included more characters, more loose ends and would have likely been about 20 minutes long. A lot of the refinement came from consolidating characters and getting rid of backstory and unnecessary exposition.

The film originally opened with a scene showing a Collateral Murder Wikileaks-style video going viral and the CIA and Air Force jointly bringing in a young PR person to solve the problem with some outside-the-box thinking. The biggest crisis to overcome in the writing stage was to restructure this opening to introduce Newton right away.

This sequence remained in the cut fairly long into production, but was then replaced with the current opening of the film, which introduced Newton and his prerogatives right there on the runway. I went for a walk and wrote out the new sequence quickly in a notebook.

The final triptych of shots at the end where the airfield of new drones gets smiley faces spray-painted on was added very close to the end of production, re-using existing assets and backgrounds, to create the mirror image of the opening shot. One of the great benefits of working on a project mostly alone is the ability to be light on your feet in conceptualizing and implementing last minute changes.

FINANCING

When the film began coming together in earnest, I decided I wanted to get serious about the scale of production. I reached out to my friend Jeanette Jeanenne, who I had been working with already for a number of years on the GLAS Animation Festival (which she founded in 2014) and had been friends with for many years prior to that. She had produced some projects for mutual friends, and I knew she was extremely organized, diligent, and fearless about diving into the more opaque aspects of making a film properly (more on that later).

With Jeanette onboard, we started brainstorming about budgets and where the financing for a project like this might come from. In the US, there is essentially zero government funding for this kind of work. Any money that might be available would either be through some kind of commercial financing, which I had already decided against, private art grants, which I began applying to, or finding a European producer.

We reached out to our friend Draško Ivezić, a writer, director, and producer at Adriatic Animation, an studio based in Croatia. At first we were just asking for advice and guidance about how the European financing system worked, but this quickly evolved into him getting involved in the project as a producer. The application for Croatian national funding was ultimately rejected, but Draško ended up being immeasurably helpful in shaping the first iteration of the script and animatic. The first draft I shared with him was over 20 pages, and he helped to consolidate characters and simplify the storytelling to ultimately get the first cut of the film under twelve minutes.

Soon after this, Jeanette and I attended Les Sommets du cinéma d'animation in Montreal as visiting artists with an invitation from the amazing Marco de Blois. We set up a pitch meeting with Jelena Popović, a producer at the National Film Board of Canada who I had met several years before at the Ottawa International Animation Festival. The trip was a huge success (and a lot of fun) and Jelena officially came on board to apply for Canadian funding. The budget was, from my perspective, huge, and the schedule was fast, only six months or so for animation. It was all very exciting.

The production was all going to take place in Canada, using Canadian animation talent. The first step was setting up a collaboration with an animation studio in Montreal. Jelena introduced us to E.D. Films, who immediately blew me away in our first conversations about their vision for how the pipeline for the film would work, specifically how to approach the animation on the drone itself (more on this below).

The trouble started when it was flagged that the top-bill creative roles were all filled by people from the US. From my perspective, this didn’t feel entirely accurate, since all of those roles (writer, director, storyboard artist, editor, lead animator) were all done by me, for free, while we were still developing the film in Croatia. I could see how this might appear problematic on a spreadsheet, but in reality felt like it shouldn’t have too much impact on the overall creative balance of the film.

The financing with the NFB would ultimately also get rejected, for reasons that were a little above my pay grade. The best part of the process was working with Jelena, who was such a champion of me and the film and put so much energy into trying to get it made, as I’m sure she does for all the films she’s involved in. We’ll work together again one day.

At this point I was feeling pretty burnt out on pursuing international financing on the film. I didn’t like having to apologize for what this movie was about, its politics, and the creative talent that I wanted to work with. And having started some of the production/pre-production on my own only made it more difficult, which was frustrating to discover. Right when the outlook was not looking good for the film, I was finally able to get two grants, the Berkeley Film Fund and the Guggenheim Fellowship. They were substantial enough for me to complete the film without any other financial help.

STORYBOARDS

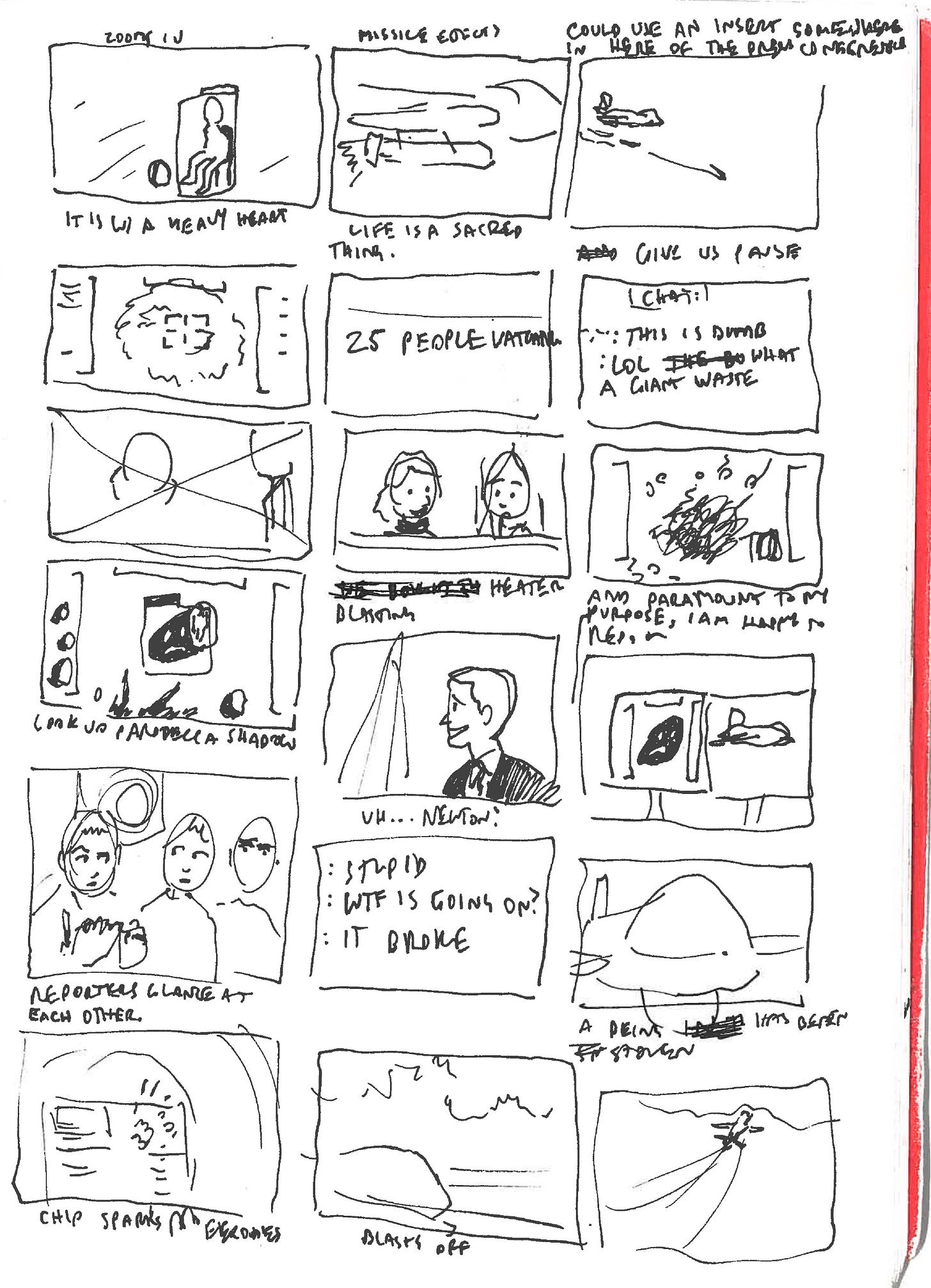

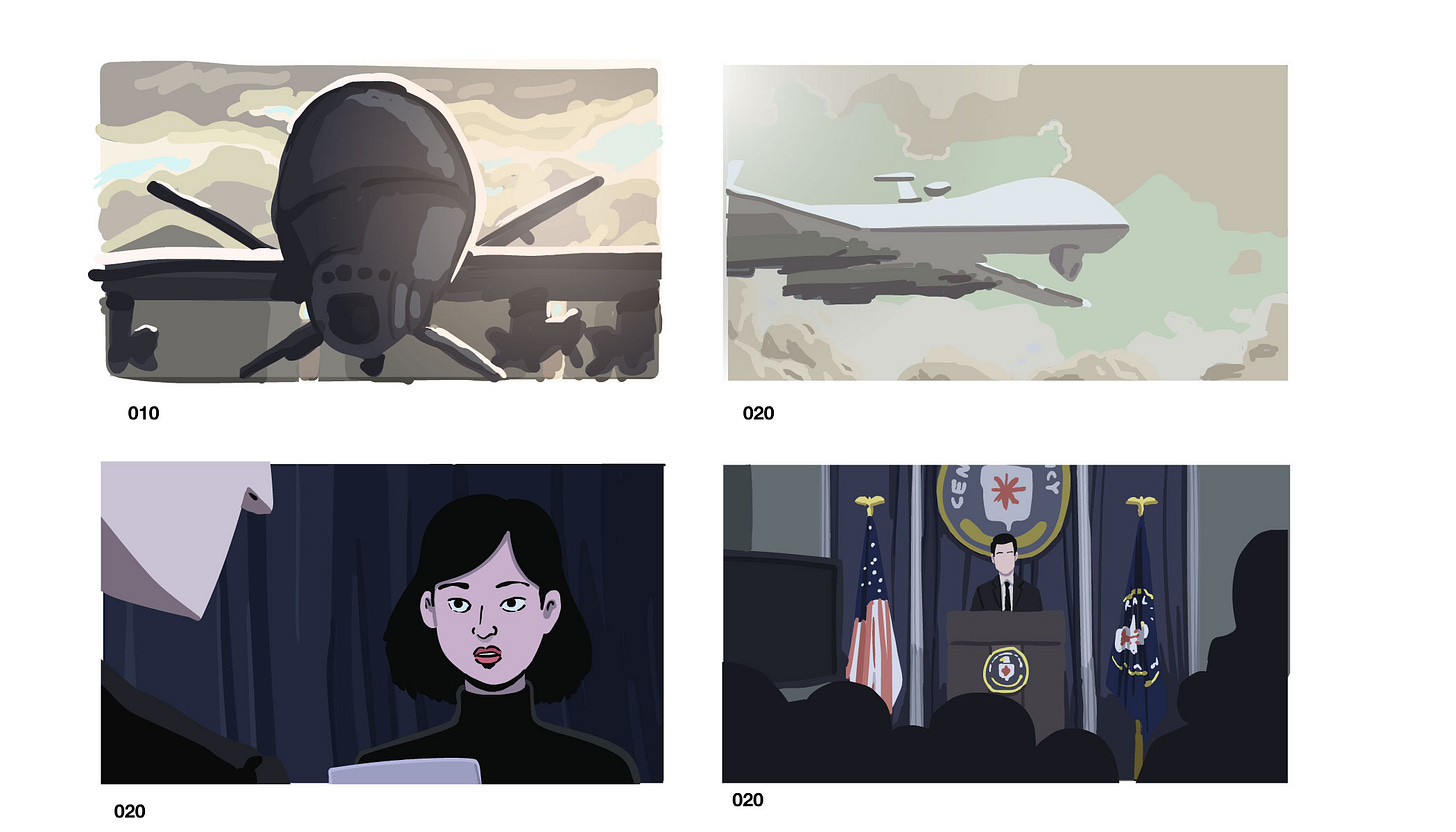

I’ve gotten into the habit of starting my storyboarding process with a really fast thumbnail pass on paper. With my previous films, I was never that serious about refining the boards much further, since I knew I would be working on the film by myself and didn’t see the point if I understood the intention from the thumbs. But for Drone, I knew other people would be reviewing the animatic and that it needed to be a lot more legible.

A key scene in the film is Newton’s first flight after going rogue. Terrence Malick is an inspiration I keep returning to, and I wanted this scene to have a similar montage quality. This made the initial storyboarding phase fun, since there didn’t need to be a lot of continuity and I could more simply explore images that felt fun. The writing for this scene was also minimal, most of it got backtracked into the script after this thumbnail pass.

This then got translated into a more robust digital board pass, adding extra poses, and dialing in the composition a lot.

Some things would continue to change between this version and the final, but I wanted to create an animatic of the whole film that could be sent to someone with little or no context and still be completely watchable. I took a lot of inspiration from observing how my friend Joe Bennett would construct his animatics, which are some of the most impressive I’d ever seen and tonally conveyed exactly what the finished film would feel like. Recording the scratch dialogue on my phone also allowed me to continue to refine the script, finding more natural rhythms for the lines before any real actors came in. The temp song is from the Phantom Thread soundtrack by Jonny Greenwood.

Jeanette and I also made a spreadsheet to track the shots, and as a way for me to track progress with the artists that joined the project later for specific sections of production.

DESIGN

Very early on in the development process, I wanted bring my old friend Alex Murray-Clark onto the project. Alex has always been one of the most gifted painters/illustrators/comic artists I’ve known, and I wanted to see how he would treat the original inspiration image of a drone flying across a romantic sky. This first image would serve two important functions, one to kick off the graphic research and tone, which at that point hadn’t really started, and second to serve more practically as a cover for the very first pitch deck.

I loved how Alex treated the image, and the color palette he developed had a big impact on the film, particularly the end.

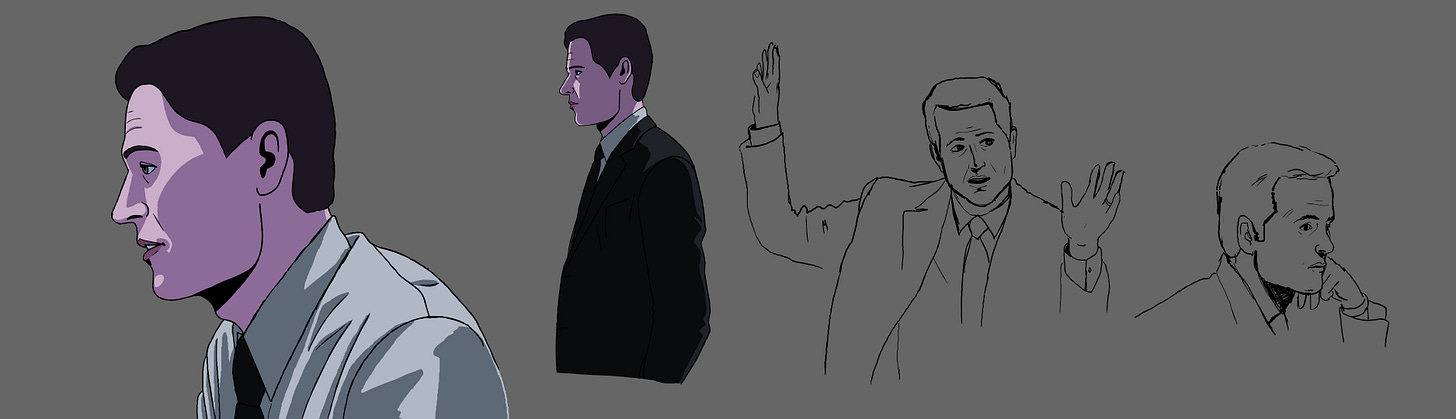

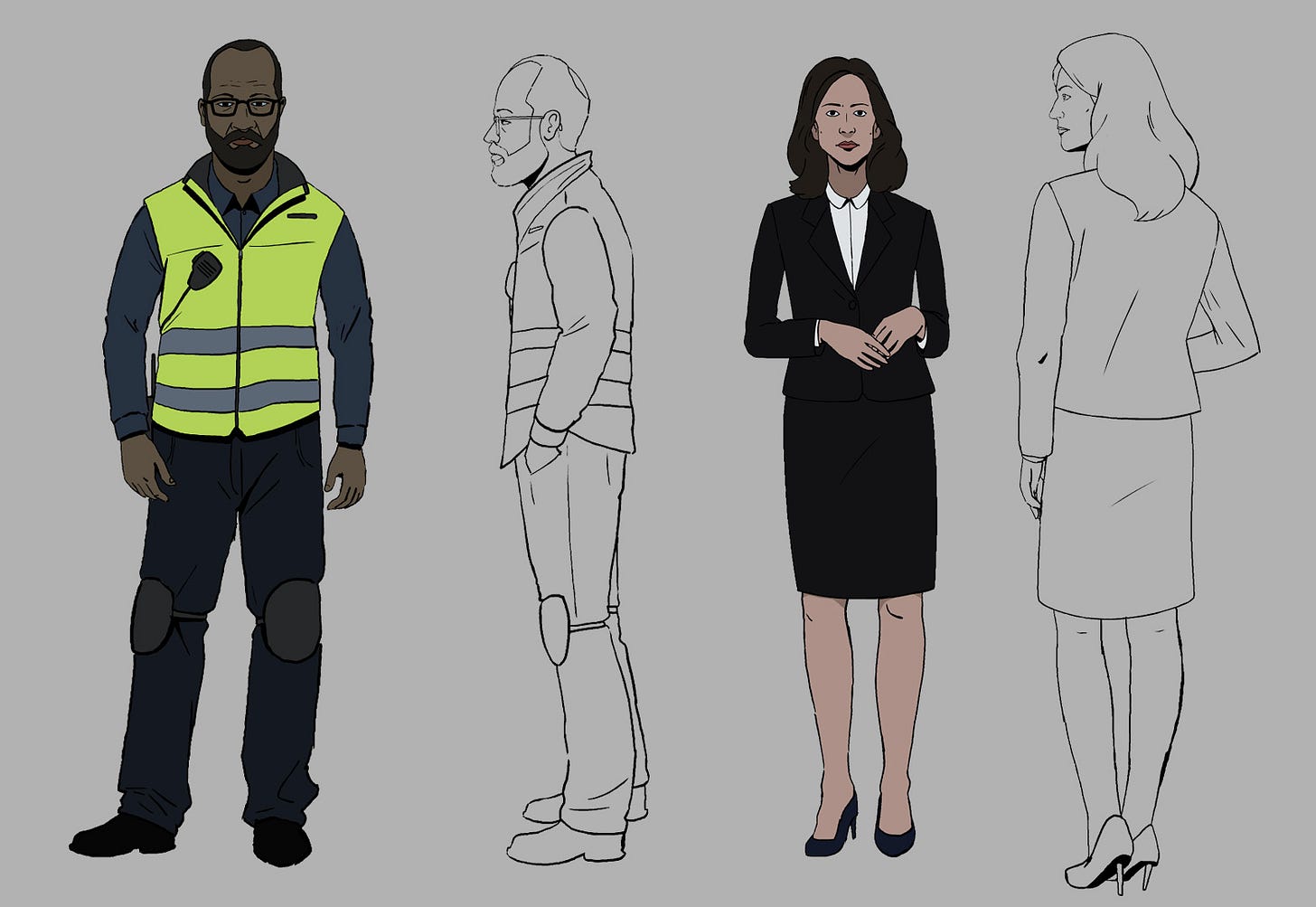

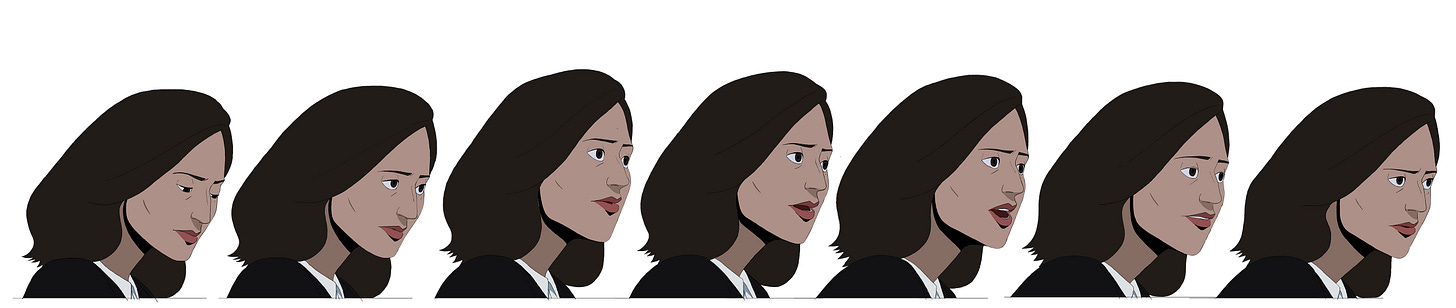

Next, I moved on to designing the characters. I don’t consider this my specialty, so I use a lot of reference of real people for each character. I find this especially helpful for what outfits the characters are wearing, and having the fits feel specific to different body types.

Once a character had been cast, I would do a new set of drawings that usually was a bit of a mix between the actor that would eventually do the voice, and the original character design. The main CIA character, still retaining the outfit and hairstyle of original drawings, suddenly starts to look a lot more like Jim True-Frost in his expressions and mannerisms.

I find that I usually rush this part of the process, and typically discover what a character looks and moves like when I start the actual animation. But this would also be the first time I would be handing off some of the character animation, and a lot of the cleanup and color, so I felt I had to be a bit more thorough (even though it was not nearly as thorough as any actual commercial productions).

CASTING

Jeanette had become a completely invaluable part of the production at this point, but the part of the process that I felt she was most essential for was in the casting. Early on, I had thought of a couple of different friends and acquaintances who could play certain roles. The plan was to do this casually, improvise lines, and record it all on my phone. I’m not sure why I was so resistant to the idea of traditional casting and recording situations; I think I naively believed that some spark would be lost doing it that way. But Jeanette had gotten very good at reaching out to people, I think primarily through her work organizing the GLAS Animation Festival, and cultivated the attitude of “the worst they can say is ‘no’”. This proved to be extremely effective.

The role of the main CIA character was written with Jim True-Frost in mind. I loved Jim in a bunch of movies, like Hudsucker Proxy and Singles, but I was most drawn to him because of his role as Roland "Prezbo" Pryzbylewski in The Wire. Jeanette reached out, and Jim said he would be in the film as long as we came to a recording studio near him in upstate New York.

On the same trip, we recorded the amazing Shirley Chen, who I had seen in my friend Danny Madden’s film Beast Beast.

Recording the actors would come in stops and starts. Just having Shirley and Jim was enough for me to get started with final animation, and it would take months before I ran out of material to animate. This was another advantage of working ostensibly by myself at this stage, as the search for the voice of Newton would take quite a while.

A slightly serendipitous turn of events led me and Jeanette to Finn Wittrock. I had seen Finn in a number of movies and TV shows, including his great part in The Big Short, but at the time we were thinking about Drone, I was watching him in the second season of American Crime Story. Jeanette was casting for a different project, and I sent her a link to an interview with Finn. She got in touch and they tried to schedule something, but ultimately Finn wasn’t available for that film. A few months later, it occurred to us that Finn would be perfect for Newton.

To me, Finn has a very well-rounded, “All-American” type of voice, that betrays a kind of innocence, but can also speak with authority. We also learned while recording him that he is classically theater trained, and had performed a lot of Shakespeare, which lent the monologues a certain amount of bravado. I couldn’t have been happier to get Finn, and he was incredibly generous to lend his acting talent to our little film.

At the end of our recording session, I had Finn record a bunch of canned Siri-style generic responses. It felt like a nice cap to the Newton character.

Jeanette’s actor friend Juan Riedinger hooked us up with Mo Collins, who blew us away with her performance. Even though her role wasn’t super joke-y, Mo had such good comic timing for her character’s switch from cold and cynical, to desperately sincere.

The last actor we recorded was Darnell Kirkwood, who plays the engineer character at the beginning of the film and came highly recommended by his wife, who Jeanette met in the sauna at LA Fitness in North Hollywood. It’s all about who you know. I loved the low key, chill energy Darnell brought to his performance, really selling the routine of this guy’s day.

Jeanette was also an essential part of doing this all properly, which involved navigating the fairly tedious bureaucracy of contracts and working with SAG. This takes a very patient, detail-oriented person, which unfortunately I am not, but thankfully Jeanette is. From my perspective, this side of things was all very smooth, but I know that Jeanette had to jump through a lot of confusing hoops, and I’ll be eternally grateful to her that we got such an amazing cast.

PRODUCTION

Soon after the animatic was complete, I began doing some very rough color studies to block in certain sequences and how the overall palette would evolve throughout the film.

While working on my previous film, I learned that I am not the strongest background illustrator. I'd been keen on expanding the creative team, and with the funding from Guggenheim I was now able to do just that, and the first person I wanted to bring on was a background designer. My friend Charles Huettner sent me a link to a young illustrator working in Portland named Wes McClain, and on his website, I saw this digital painting he had done.

I knew instantly that he was a perfect fit, not only in how masterful he was at painting, but also a sensibility that could capture the specificity of the real world in such a particular way. My rough color board drawings immediately fell off, since Wes was able to do such a good job of amalgamating different references and rendering it all with such beauty. Reflecting on it now, bringing Wes onto the project was probably the single most pivotal moment for how the film would ultimately turn out. I quickly learned that I had to animate in a completely different way, and had to learn a lot more about compositing, so the characters felt like they were actually living inside the world the backgrounds created, and not just floating, pasted on top.

Wes posted more backgrounds from the film on his website.

Once Wes had completed the backgrounds, one of the biggest challenges was finding an animation and compositing style that would match the lighting and detail. I felt I reached a happy medium, particularly in shots that had more stylized lighting, to achieve some kind of sustainable final color that was still dynamic enough to feel natural in specific lighting settings.

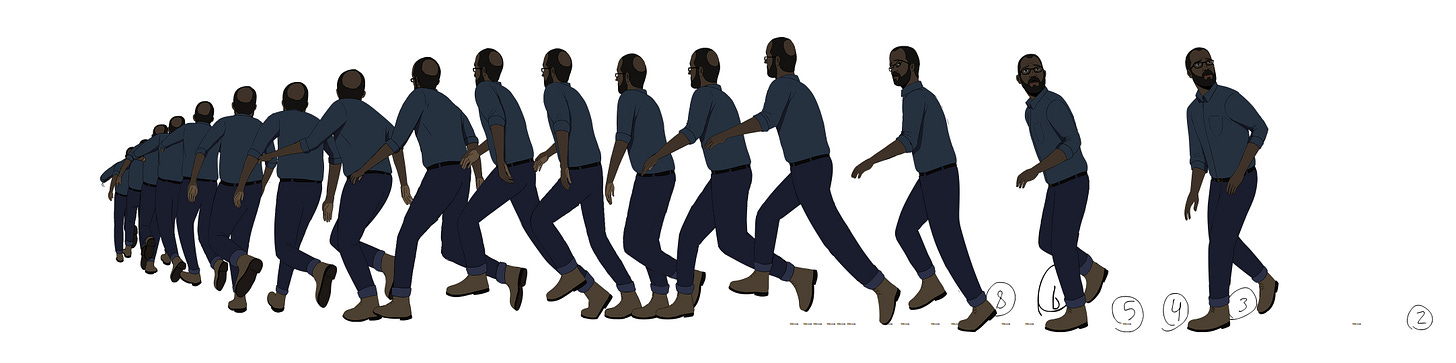

My style of animating also got a lot more complex on this film compared to my previous short. I really wanted to articulate the acting and bring a lot of subtlety to the gestures and movement. This aspect was by far the most time-consuming on production, since almost every single shot with a character speaking had basically wall-to-wall fresh frames.

I did use some techniques to simplify this. One was always separating the head and the body, so the lip sync and expressions could get dialed in more specifically, and facial features could get inbetweened more seamlessly. The head would then be attached frame by frame. I would also typically go from rough keyframe drawings and breakdowns straight into cleanup line work. This also saved a lot of time. Part way through production, Kyle Brooks joined the project to help with cleanup and color. By the end of the film, Kyle had improved so much as an animator that I was able to hand off a lot more full animation work to him.

Vincent Tsui also came on board near the end of production to animate all of the sequences with the second CIA character. Vincent is one of the most talented animators I know, and I loved his interpretation of this character. The dimensionality and volume of his drawings made simple shots really come to life with expressiveness. Vincent joining helped massively accelerate the completion of the character animation.

Early on in production, I was under the assumption that I would be doing most of the actual animation myself. I wasn’t worried about the character animation, but I knew that animating the drone itself was going to be a challenge. The storyboards called for a lot of dynamic movement, and the realism I was after would require very technical animation to keep the drone on model, so I knew doing it freehand wouldn’t work.

My solution was to buy a license for Cinema4D and a model of a predator drone from Turbosquid. I taught myself just enough about animating and rendering in 3D to produce an image sequence with a black outline:

I then imported this as an image sequence into Adobe Animate and traced the black outline on 2s. I used the shadow from the 3D render and composited the drone onto Wes’ first background test. The result was promising in a way, but took so long to complete that it immediately felt unsustainable. Plus, there were technical issues with the drone animation strobing with the camera move, and it was going to be impossible to trace every frame of the 3D.

I produced one additional test in this style before reaching the final conclusion that it was an untenable process and that the drone would need to be rendered fully in 3D (and I didn’t even finish coloring the shot it was so tedious). As much as this felt like a waste of time, it was a valuable learning experience for how the finished look of the drone would integrate with the character animation and backgrounds.

At the time, we were in the process of collaborating with the NFB, and we started having our initial conversations with Daniel Gies at E.D films for the technical animation pipeline. For the drone itself, he was very confident that we could replicate the undulating line I had been doing in my tests using Grease Pencil in Blender. They did a few tests that perfectly simulated the look and I was completely relieved that this was all gonna work. Then our NFB financing fell apart and we lost E.D. as our production studio.

A few months passed, and it occurred to us that, since E.D. had already done so much development on the drone animation pipeline specifically, maybe it would be possible to re-approach them to just animate the drone itself and nothing else. They were game and we implemented a pipeline that primarily involved me working directly with Eric Max Kaplan, a fantastic animator and technical wizard. I’ve since worked on another project with E.D. and hope to work with them for as long as they want to work with me.

Near the end of the project, a couple of freelancers came on board the project to do some specialized animation work. First was Nicole Stafford, an animator whose work I had always admired, especially the animation she had done while studying at Gobelins on the short Wildfire. She would do all of the effects animation in Drone.

Then David Delafuente joined the project to design the Drone HUD and the “eye” of Newton, which could show Newton’s various modes like “thinking” and “listening”. I sent David some reference from devices like the Google Home, which had amazingly simple and intuitive light animations to represent its various processes. David did such a good job creating a simple but effective way for Newton to speak and emote. I think this also anthropomorphized Newton in an interesting way, since the camera rig is really his head, but the front of the hull becomes his face later once the smiley is spray-painted on.

And just like that, production was done. Admittedly, there were a lot of emotional ups and downs getting through the bulk of the character animation. It felt like running a really, really long marathon with no end in sight. The biggest psychological hurdle was always “If I don’t work really hard on this every day, it’ll never get done, and worse, no one will care that it’ll never get done”.

STUDIO

I animated most of the film in my small Los Angeles apartment between 2019 and early 2021. I mostly used the Adobe software suite: Animate for the animation and After Effects for the compositing. I was working on a 2014 iMac, which I ran into the ground while making this film, and a 22 inch Wacom Cintiq, which is one of the best pieces of hardware ever made.

The middle part of production was carried out during a three month residency at The Animation Workshop in Viborg, Denmark, where it was dark most of the time, and there wasn’t much else to do besides animate.

MUSIC & SOUND

Drone would mark my fourth collaboration with the musical geniuses Skillbard (aka Vincent Oliver and Tom Carrell). From the outset, they had big ambitions for recording an orchestra for the Drone score, which was very exciting to me. But even their earliest spotting tracks nailed the tone of the film, and working with them was, as always, a real joy. I invited them to document some of their behind the scenes experiences working on the film:

Noun: A Deep Sustained Or Monotonous Sound

Drone is concerned with some pretty lofty concepts and we wanted to be sure we fully understood Sean’s point of view before we dove in, so we requested a reading list and pounded through some relevant literature in front of a log fire on our Christmas break. We found Frankenstein to be the most fruitful reference, paralleling so many of the key ideas in Sean’s script in an equally lyrical way.

To kick us off, Sean sent us a WIP along with some spotting notes. In true Buckelew fashion, they were fun & casually worded but extremely well thought-out.

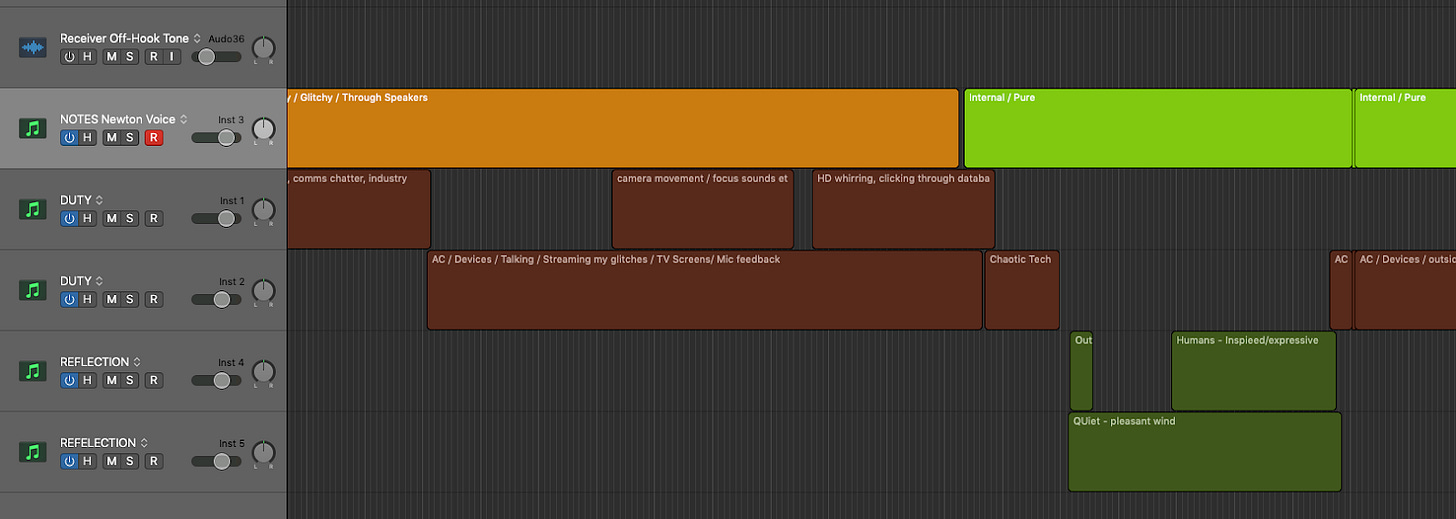

His first note: “Overall, I think the sound/music oscillates between two modes: one is kind of bureaucratic and banal, the other is dreamy, impressionistic and poetic” presented to us the idea of a duality at the heart of the story. So, borrowing a technique from David Sonnenschein’s book Sound Design: The Expressive Power of Music, Voice, and Sound Effects in Cinema, we plotted a table of two columns with relevant motifs aligned with the two main ‘modes’ that Sean discusses. We thought the film a little too nuanced to label “good vs evil” or “man vs machine” so we decided upon the much broader terms “Inside” & “Outside” to name the two forces.

Our “Bipolar Evaluation” of Drone:

We then mapped out the timeline of the film with colour-coded slugs that tracked the two main polarities to help us plot the emotional beats of the story arc, forming a solid guide for us to follow while we worked.

A couple of weeks later, we presented our first sketch to Sean: We went big from the outset, unabashedly invoking signifiers from the sub-genre of ‘hollywood flying music’, Namely: a soaring melody, vivid chordal gestures, and rich, lush strings over a floaty waltz feel. This OTT feeling seemed to elevate Newton’s monologue into the realm of fantasy, contrasting with the cold cynicism of the office scenes.

In a previous collaboration with Sean, Lovestreams, we relished the opportunity to create an Enya-inspired, floating & ethereal ‘semi-New Agey’ score that could perform on a dual level: Being playfully ironic while legitimately tugging at heartstrings. We approached Drone with a similar sensibility.

Sean’s response was very enthusiastic: “you guys are fucking brilliant, skillbard strikes AGAIN!!!!”. Smashed it first time!

But really all credit goes to Sean for making it easy to get right. When a filmmaker understands their message, thinks things through as thoroughly as Sean does, and takes the time to communicate so effectively with collaborators, it starts to feel like all we need to do is go away and start pressing the buttons. He had notes, of course, but nothing major, so we pressed on, fleshing out our demo and writing cues for the rest of the film, sending regular WIPs to Sean for his thoughts. We also started work on the sound elements, focusing mostly on the bombing scene to establish overall dynamics of the film, since that’s the loudest/most intense bit.

Now we had established the musical DNA for Newton’s journey and we set about extrapolating, variating and developing outwards to set up the other cues.

EG During Newton’s death cue we rendered a sombre, minor-key variation from the core motif.

As usual, music was the most noticeable emotional & atmospheric signifier but every sound you hear was considered in terms of how it contributed to the story emotively, narratively & even conceptually. Perhaps the most obvious example is processing of the dialogue EG: a feeling of alienation was often achieved through tactical intelligibility of dialogue. It’s not always clear what Newton is trying to tell us while he’s delivering his manifesto because, ultimately, it was never heard or understood outside of creating a spectacle.

Similarly, a lot of the dialogue in Drone is heard through speakers, we’re not sure if this is something we discussed with Sean but our perception was that this was an expression of technology’s power to create distance between people. It seemed important that this is something that is felt by the audience. We did a lot of ‘reamping’ by hacking gritty, small speakers to make this talker—>listener detachment palpable.

Once all the music was written and demoed and approved by all parties, we sent our sample-based mockups to our talented orchestrator Finn McNicholas (Midsommer, Daniel Isn’t Real, Swansong) and briefed him on how we’d like them to end up when played by the orchestra. Finn listened carefully to what we’d programmed in MIDI, transcribing it to page to achieve everything we were expressing in a way a room full of 30 people can understand and play without complication.

To invoke Newton’s destructive intentions, Finn helped us pin down and notate a number of ‘extended techniques’ for our orchestra to try; often ‘unmusical’ playing styles that push the instruments outside of its regular usage into more savage tones.

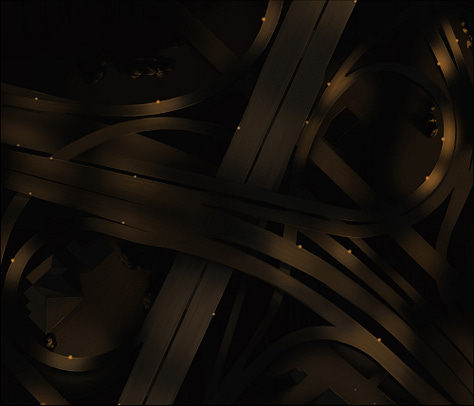

This musical thread begins during the night time cue ‘Alienation.’ Newton’s monologue describes an “interwoven fabric” while we see a spaghetti junction. We wrote a long sustained drone featuring an airy random textural movement from the string players, giving a musical sense of threads rubbing together.

Later in that cue when Newton describes the destruction he is about to bring forth while we see a field in flames, we wrote two powerfully opposing chords with a tense and nervous tremolo, going between ‘sul tasto’ (string player playing close to the neck) and ‘sul pont’(string player playing close to the bridge) to express his destructiveness and contradictory nature.

In the death scene after he crashes we hear a scratchy gnarly string articulation, Newton’s full destructiveness wrought…

When we had worked through exactly what we wanted with the orchestration, we attended and directed the session with the Budapest Art Orchestra (Queen’s Gambit, Locke & Key, Godless).

A portrait of two composers and orchestrator on the day of recording.

Covid prevented us from attending the session personally—which was a shame because a pint of beer in Budapest is like £2!

Unfortunately their live room camera fell over immediately upon starting our session so this is the best angle we have.

Enjoy the entire soundtrack below:

RELEASE & CONCLUSION

Drone world premiered in June, 2022 at the Annecy International Animation Festival.

Attending Annecy was a lot of fun. It had been ten years since I’d been there in 2012 when I helped curate a program of CalArts student films. During the screening of Drone, I had a slight nagging feeling that the density of dialogue and text made some of the subtlety and humor not land quite as well as I had hoped, particularly in the close ups of the live chat. This was semi-confirmed when the film played a few months later at the Ottawa International Animation Festival, and got a lot more audible response in the comedic moments. But it’s difficult to read an audience reaction, and I think people over-laughing can also be a problem sometimes at festival screenings, so all-in-all I think it balanced out well.

So why make an animated short? Honestly, I don’t really know. Has Drone allowed me to meet a lot of new people and initiate new creative collaborations? Definitely. Was it fun to make? Some of the time, but not always. Has it seamlessly helped set up my next projects? Not exactly, but probably to some extent. But is that the reason to make a short? Hopefully it justifies itself as a standalone form of expression, but it’s hard not to rationalize things in practical, validating terms like success versus failure.

At the end of the day, I enjoyed making Drone and I hope you enjoyed watching it. Those are the two things that matter.

Eu gostei muito deste curta metragem foi muito bem feita seria melhor ser tive tipo uma série contando mais

Thanks so much for this in-depth behind the scenes, Sean! The movie is so good. Trying to make a short as well. And because the process is so difficult, it's great to feel inspired by other animators.